Public Opinion

Dr. Christopher N. Lawrence

Middle Georgia State University

POLS 1101: American Government

🔊 Disable Narration

Overview

What is public opinion?

Where does it come from?

How do we measure it?

What is the role of public opinion in politics?

What is Public Opinion?

V.O. Key defined public opinion as reflecting “those opinions held by private persons which governments find it prudent to heed.”

Another definition: the collective or aggregate opinions of the adult population.

The Origins of Public Opinion

-

Emerges in part from the political socialization process in childhood and early adolesence:

Family

School

Religion

Community

Socialization helps form beliefs and values that shape our opinions later in life.

Influences Later in Life

-

Opinions are also influenced by adult experiences:

-

Self-interest

-

Employment

-

Property ownership (stakeholding)

-

Parenthood, marriage

-

-

Higher education

Instills tolerance and other political values.

Increases political efficacy: the belief that one's actions can affect government policies.

Mass media

-

Tolerance Effects of Education

Measuring Public Opinion

Before the 1930s, studies of public opinion relied on convenience samples or straw polls.

-

1930s: George Gallup developed the scientific approach to survey research still used today:

Use of random samples.

Efforts to reduce selection bias.

Another consideration is measurement error: expressed opinions may not reflect underlying attitudes.

Random Sampling and Sampling Error

In a random sample, each member of the population of interest has an equal chance of being surveyed.

-

This rule guarantees that the sampling error—the error in polls due to using a sample rather than looking at the whole population—is as small as possible.

-

Bigger samples have less sampling error:

500 respondents: ± 4.4%

1000 respondents: ± 3.1%

-

Selection Bias

If some members of the population are more likely to be surveyed than others, selection bias results.

-

Sources of selection bias:

-

Sampling frame is not the population of interest.

Telephone polls omit people who don't have phones.

-

Nonresponse bias.

Some groups of people are less likely to respond to surveys than others.

Self-selection (opt-in), common in web polls

-

Measurement Error

-

Another common problem: survey questions may not accurately gauge interviewees' true attitudes:

Many opinions cannot be measured objectively and are hard to quantify.

Questions may lead to biased responses due to their wording.

Attitudes may be too complex for a single question.

Confusing Question Wording

-

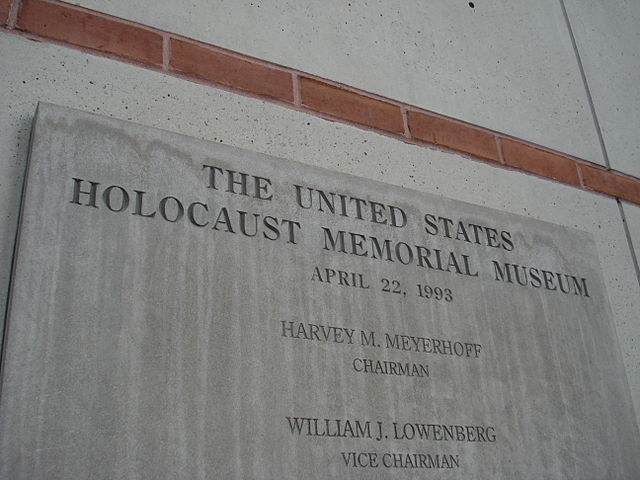

In 1993 the American Jewish Committee commissioned a survey on public beliefs about the Holocaust when the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in Washington.

22% of Americans said it was “possible… the Nazi extermination of the Jews never happened.”

Confusing Question Wording

-

Question asked:

“Does it seem possible or does it seem impossible to you that the Nazi extermination of the Jews never happened?”

Question was not clear or simple; it contains a double negative.

Confusing Question Wording

-

Alternative question used in a subsequent poll:

“Do you doubt that the Holocaust actually happened, or not?”

In this formulation of the question, 87% of respondents were certain it happened and only 9% said it did not (4% were uncertain).

The full report, by David W. Moore and Frank Newport, is available in The Public Perspective (March/April 1994).

Value-Laden Wording

Sometimes these differences can emerge based solely on the terms used in the question:

| Question | Too little | About right | Too much |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spending on “welfare” | 25% | 37% | 38% |

| Spending on “caring for the poor” | 70% | 22% | 8% |

| Source: 1984 General Social Survey. | |||

Oversimplified Questions

Some issues are too complex to be captured by a single survey question.

-

Attitudes towards abortion are a classic example:

Many Americans are not neatly “pro-choice” or “pro-life” in all circumstances; instead they tend to fall in the middle.

Questions about the extremes lead to biased responses that don't reflect issue's complexity.

Abortion: A Complex Issue

Public Opinion and Government

-

While many of the sampling and measurement issues can be overcome, there are other obstacles to “governing by public opinion”:

Voters are uninformed.

Voters lack ideological constraint.

Voters' attitudes are unpredictable.

Political Information and Rational Ignorance

Voters will express opinions about things they know little about.

A small fraction of the public knows “basic” information about politics like the identity of the Chief Justice of the United States or the Speaker of the House.

Voters are rationally ignorant: they know little about politics because the benefits do not exceed the costs.

Americans Lack Political Knowledge

Exceptions to Rational Ignorance

Higher education leads to more knowledge.

Personal or group interest leads to acquiring knowledge about relevant topics: issue publics.

Important events and media publicity may increase knowledge for a time.

Ideology and Unconstrained Beliefs

-

Political elites (people who are deeply interested and involved in politics) tend to conceptualize the world using ideologies:

Liberals

Conservatives

Ideologies help people shape the political universe and connect related ideas together.

Most people (the mass public) don't think about politics in these terms.

Attitude Inconsistency

-

Attitudes of the mass public often reflect logical contradictions:

Support for cutting government spending in the abstract, but opposition to cutting spending on specific programs.

Support for expanding government programs and cutting taxes at the same time.

Support for “free speech” but opposition to the exercise of free speech by unpopular groups.

Opinions and Governing

-

Even when the public cares deeply about an issue, government action may still be unlikely:

Senators and representatives are responsible to their local constituents, whose opinions may differ from the public at large.

Elected officials may be more concerned about their supporters and single-issue voters than all of their constituents.

Elected officials may believe that voters have other, more important priorities.

Collective Rationality?

Despite the shortcomings of the public, government policy does seem to respond to aggregate trends in opinion.

While individual opinion often appears irrational, collective opinion seems to cancel out much of the noise: the “rational public.”

Public can use heuristics or shortcuts to form opinions with limited information, including party identification.

Copyright and License

The text and narration of these slides are an original, creative work, Copyright © 2000–25 Christopher N. Lawrence. You may freely use, modify, and redistribute this slideshow under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA.

Other elements of these slides are either in the public domain (either originally or due to lapse in copyright), are U.S. government works not subject to copyright, or were licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license (or a less restrictive license, the Creative Commons Attribution license) by their original creator.

Works Consulted

The following sources were consulted or used in the production of one or more of these slideshows, in addition to various primary source materials generally cited in-place or otherwise obvious from context throughout; previous editions of these works may have also been used. Any errors or omissions remain the sole responsibility of the author.

- Barbour, Christine and Gerald C. Wright. 2012. Keeping the Republic: Power and Citizenship in American Politics, Brief 4th edition. Washington: CQ Press.

- Coleman, John J., Kenneth M. Goldstein, and William G. Howell. 2012. Cause and Consequence in American Politics. New York: Longman Pearson.

- Fiorina, Morris P., Paul E. Peterson, Bertram D. Johnson, and William G. Mayer. 2011. America's New Democracy, 6th edition. New York: Longman Pearson.

- Krutz, Glen, et al. 2025. American Government, 4th edition. Houston: OpenStax College.

- O'Connor, Karen, Larry J. Sabato, and Alixandra B. Yanus. 2013. American Government: Roots and Reform, 12th edition. New York: Pearson.

- Sidlow, Edward I. and Beth Henschen. 2013. GOVT, 4th edition. New York: Cengage Learning.

- The American National Election Studies.

- Various Wikimedia projects, including the Wikimedia Commons, Wikipedia, and Wikisource.