Congress

Dr. Christopher N. Lawrence

Middle Georgia State University

POLS 1101: American Government

🔊 Disable Narration

Congress: The Legislative Branch

In comparative perspective, Congress is unusual.

Most legislatures, particularly in parliamentary systems, are relatively weak.

Congress exhibits symmetric bicameralism: both chambers roughly equal in power.

Exceptions to Symmetry

| Area | House | Senate |

|---|---|---|

| Term of office | Two years | Six years (staggered) |

| Revenue and spending bills | Can introduce or amend | Can amend only |

| Removal of officials | Votes on impeachment | Votes on removal and disqualification |

| Presidential appointments | No role | Confirms by majority vote |

| International treaties | No role | Ratifies by ⅔ vote |

Reapportionment and Redistricting

-

Every ten years, reapportionment of House districts between states takes place after the Census.

State legislatures then engage in redistricting to assign district boundaries.

Gerrymandering is often used to create districts that favor a particular party or bloc of voters.

Elections to Congress

Representatives and senators can face the voters in varying circumstances:

In presidential election years, members of the winning candidate's party can ride the coattails of their presidential nominee.

In midterm election years, voters who oppose the incumbent president tend to be more motivated to vote; president's party tends to lose seats in Congress (midterm loss).

Death or resignation of a representative triggers a special election.

Most states allow senators to be replaced by a gubernatorial appointee until the next federal general election; person elected completes remainder of the original six-year term.

Models of Representation

Contrast made by British-Irish philosopher and politician Edmund Burke in 1774, who feared tyranny of the majority as did many of the American founders.

Delegate: a representative should act according to the views of a majority of his or her constituents.

Trustee: representatives should act based on their best judgment, regardless of popularity.

Most modern politicians follow the politico model, combining elements of both.

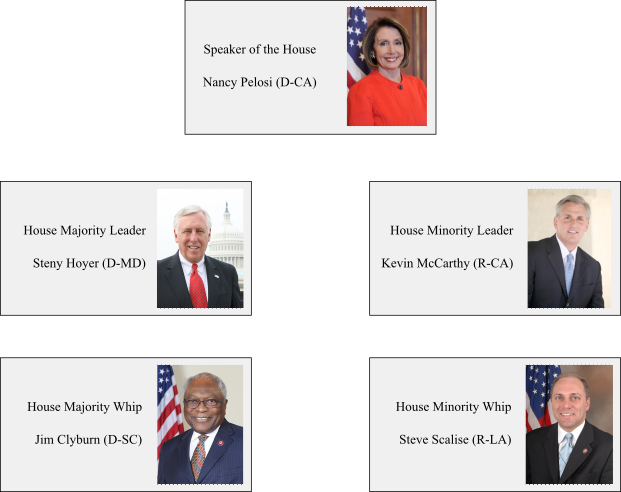

House Party Organization

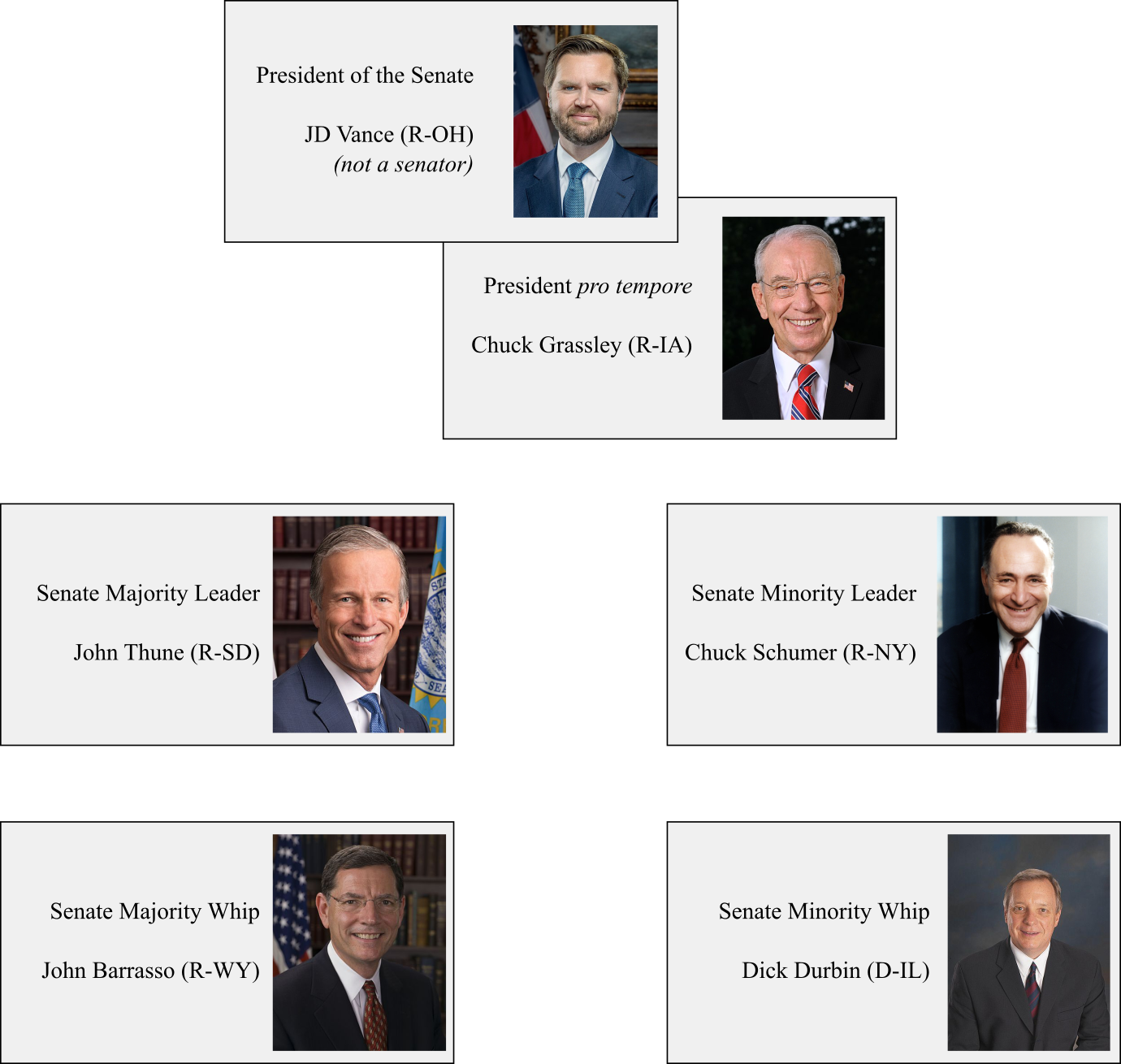

Senate Party Organization

Power of parties in the House

Committee chairs historically powerful until 1970s.

-

Power of committees diminished since:

1974 “Watergate class” reforms increased power of subcommittees; seniority system was weakened.

1994 GOP reforms: more power given to speaker; term limits for Republican committee chairs.

When parties are unified or have small majorities, members more willing to cede power to speaker – conditional party government.

Power of parties in the Senate

Parties are always weak in the Senate.

Party leaders in the Senate are more like administrators than bosses.

Committees are also weak in the Senate.

Individual senators have much more independent authority than members of the House.

The Committee System

Most work in Congress is done in committees.

Key responsibilities: lawmaking and oversight.

-

Types of committee:

Standing

Select or special

Joint

Conference

Most standing committees have multiple subcommittees that specialize even more.

More on Committees

The majority party holds a majority of seats on all committees except the Ethics committees.

Most senior majority party member is chair; minority party has ranking member.

-

Why committees?

Distributive theory: members serve on committees relevant to their districts and use positions to trade favors with other lawmakers.

Informational theory: committees help divide the workload of Congress and allow gains to the whole from division of labor.

Support Staff

-

Congress employs about 24,000 people:

Members, their personal staff, and committee staff.

The Library of Congress, including the Congressional Research Service.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO).

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

The Lawmaking Process

Bills are introduced by a sponsor.

Bill then referred to relevant committee; usually referred to a particular subcommittee.

Subcommittee may hold hearings on the bill, then mark up the bill (propose amendments).

Full committee then may also have hearings and mark up.

If the bill passes, then it will be reported to floor.

On the floor in the House

Trivial bills may be considered as part of the consent agenda and will be approved unanimously along with other bills.

Bills may also be considered under suspension of the rules – 40 minute debate; no amendments; bill must get ⅔ vote to pass.

Controversial bills will be considered using a rule issued by the Rules Committee; sets length of debate and specifies what amendments allowed.

On the floor in the Senate

Noncontroversial bills may be approved by unanimous consent.

Other bills require senators to work out a unanimous consent agreement (similar to a rule in the House) to limit debate and amendments.

If no UCA, Senate rules allow unlimited debate and unlimited amendments on most measures.

Unlimited debate in the Senate

Unlike the House, the Senate has no general limit on how long debate can continue.

Any senator who wants to block a bill or motion can filibuster – continue debate as long as he/she physically can (record is over 24 hours!).

-

60 senators can vote to end debate (cloture).

-

Even the threat of a filibuster – called a hold – will usually stop a bill from being considered.

Let's do it again!

Once either the House or Senate has approved a bill, the other chamber must also approve it – going through the complete process again.

-

To send a bill to the president, the House and Senate must agree on the exact same bill.

One chamber can amend its bill to be the same as the other's.

The chambers can appoint a conference committee to work out a common bill.

Upon receiving a bill…

-

President can sign the bill into law.

-

President can veto the bill.

House and Senate can override with a ⅔ vote in each chamber.

-

After ten days (excluding Sundays):

If Congress is in session, the bill becomes law without the president's signature.

If Congress is not in session, the bill does not become law (pocket veto) – Congress cannot override.

Authorization and appropriations

Most bills are authorization bills allowing the government to carry out certain policies for several years.

-

Any law that requires money to implement its provisions also requires a matching appropriation to be passed by Congress every year.

Congressional Careers

Serving in Congress is now seen as a long-term job rather than short-term service.

-

Members more in contact with their districts than historically was the case:

Better communications technology.

More accountability (recorded roll-calls, campaign finance information).

More frequent travel to districts.

Franking privilege borders on campaign activity.

More on Congressional Careers

-

Members today focus more on pleasing constituents than their parties.

Staff focus on ombudsman role and casework.

Pork-barrel spending (although opportunities declining).

Casework and pork are popular with constituents, even those inclined to support other parties.

Fenno's Paradox: citizens dislike Congress but like their representatives and senators.

Critiques of Congress

A highly inefficient institution – by design!

Process favors the status quo; allows determined minorities to block majority will.

-

Diversion of government resources to provide “pork” for home districts rather than nationally beneficial policies.

Copyright and License

The text and narration of these slides are an original, creative work, Copyright © 2000–18 Christopher N. Lawrence. You may freely use, modify, and redistribute this slideshow under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA.

Other elements of these slides are either in the public domain (either originally or due to lapse in copyright), are U.S. government works not subject to copyright, or were licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike license (or a less restrictive license, the Creative Commons Attribution license) by their original creator.

Works Consulted

The following sources were consulted or used in the production of one or more of these slideshows, in addition to various primary source materials generally cited in-place or otherwise obvious from context throughout; previous editions of these works may have also been used. Any errors or omissions remain the sole responsibility of the author.

- Barbour, Christine and Gerald C. Wright. 2012. Keeping the Republic: Power and Citizenship in American Politics, Brief 4th Edition. Washington: CQ Press.

- Coleman, John J., Kenneth M. Goldstein, and William G. Howell. 2012. Cause and Consequence in American Politics. New York: Longman Pearson.

- Fiorina, Morris P., Paul E. Peterson, Bertram D. Johnson, and William G. Mayer. 2011. America's New Democracy, 6th Edition. New York: Longman Pearson.

- O'Connor, Karen, Larry J. Sabato, and Alixandra B. Yanus. 2013. American Government: Roots and Reform, 12th Edition. New York: Pearson.

- Sidlow, Edward I. and Beth Henschen. 2013. GOVT, 4th Edition. New York: Cengage Learning.

- The American National Election Studies.

- Various Wikimedia projects, including the Wikimedia Commons, Wikipedia, and Wikisource.